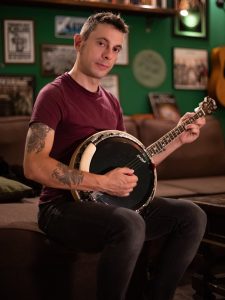

Tenor Banjo

Ita

Il “Banjo”, strumento di origine africana, era suonato già all’inizio del 17 secolo in America dagli africani in schiavitù ma fu introdotto in Irlanda ed Inghilterra attorno alla metà del 19° secolo, probabilmente quando i Virginia Minstrel di Joel Walker Sweeeney (1810) arrivarono dagli States all’Irlanda per diffondere la propria musica, contribuendo enormemente alla diffusione del banjo in Europa.

Dalle prime corde in budello e ai manici senza tasti (fretless) si passò all’inizio del secolo alla corde in acciaio che consentirono ai banjoisti di sperimentare nuove tecniche , nuove accordature ed uno uso differente dello strumento. E’ in quegli anni che molti musicisti irlandesi cominciarono ad eliminare la quinta corda e, grazie all’accordatura per quinte come nel violino e nel mandolino, ad utilizzare il banjo per eseguire un repertorio prettamente irlandese.

Il banjo tenore ha abitualmente 19 tasti ma può esistere anche in scala corta a 17 tasti. L’accordatura irlandese mantiene gli intervalli di violino e mandolino ma è trasportata una quinta più in basso: GDAE. In alternativa è diffusa l’accordatura CDAE.

La prima registrazione “commerciale” risale proprio all’inizio del 1900 grazie a Mike Flanagan (da Waterford), che iniziò a suonare sul mandolino ma – come molti altri suoi conterranei – una volta emigrato negli States passò al banjo perché semplicemente… era l’unico strumento che aveva a disposizione!

Grazie al boom commerciale dei The Dubliners negli anni ’60, il banjo tenore raggiunse il proprio apice di successo nella musica irlandese, sia per quanto riguarda i tunes sia le ballads. Barney McKenna, fu infatti il principale responsabile a diffondere l’accordature GDAE e l’utilizzo di “ornamentations” tipico del fiddle su uno strumento a corda, poi portate a nuovi livelli di tecnica da virtuosi quali Gerry O’Connor, Enda Scahill, David McNevin.

Eng

The early origins of the instrument, now known as the banjo, are obscure. That its precursors came from Africa to America, probably via the West Indies, is by now well established. Yet the multitude of African peoples. languages and music make it very difficult to associate the banjo with any specific African prototype.

It was during the end of 18th century that the banjo was introduced to Ireland, when the Virginia Minstrels toured in England, Ireland and France.

The earliest Irish banjos were definitely fretless; things changed dramatically at the turn of the century when steel strings were invented. Influenced by the use of the plectrum in mandolin playing, banjo players started experimenting with different plectral playing styles. The idea of tuning the banjo in fifths, just like the mandolin (or fiddle) caught on around this time as well. Many players started to remove the short drone 5th string from the banjo.

Undoubtedly, the first Irish banjo player to record commercially was Mike Flanagan, born in Co. Waterford in I898, who emigrated to the United States at the age of ten. Like many Irish banjo players, he started on the mandolin and learned on his own simply because there was no one to learn banjo from. Mike recorded prodigiously with his brother Joe, accompanied, during the early years, by another brother Louis, who passed away at a young age.

Other banjo players to record in the I920s were Michael Gaffney from New York and the late Neil Nolan from Maine, who played with Dan Sullivan’s Shamrock Band in Boston. There was great life and exuberance in these early recordings, in part because the music was designed for lively dancing, but also because the banjo was at that time traditionally tuned higher than it is nowadays – still in fifths, but with the top string pitched at Bor sometimes even at C.

In the early I960s the meteoric rise to commercial success of The Dubliners in the Irish and English folk revival was to have a profound effect on the fortunes of the banjo in Irish music. Bearded, affable Barney McKenna, ace tenor banjoist in the group, became a household name among among traditional music fans. Barney’s skills and wide visibility helped bring scores of new devotees to the instrument, almost all tuning their banjos as Barney did -G D A E – an octave below the fiddle. Now there are literally hundreds of accomplished Irish banjo players in Ireland, England and America. The instrument has most certainly come of age, after years of occupying a marginal position in traditional music.

Source: Mick Maloney